Return to the Stevens Family Travel Archive

Back to the Hiking page

|

|

Mountain Rain: A tale of hiking in OmanBy Vance Stevens

|

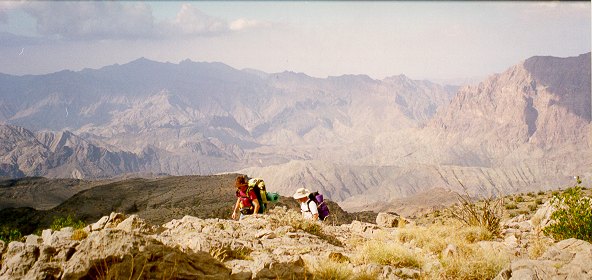

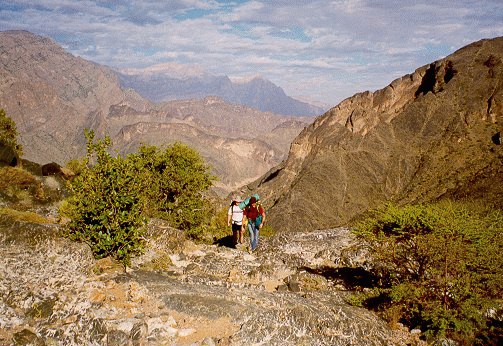

This is an account of a solo jaunt I made in 1992, without a camera. Then in October 1998, some friends in Abu Dhabi (Mike Douglas, Paul Briggs, and his visiting cousin Mike) wanted to go for a stroll in Jebel Akhdar, and I suggested the picturesque walk up from Hat in Wadi Bani Khurus to Aqabat Dhufur. We had intended to replicate the walk recounted below, but we ran short of water at Aqabat Dhufur and conservatively decided to retrace our steps to Hat rather than push on to Aqabat Talhat. I realized then that the reason I was able to make the walk I did, to stay out 3 days in the mountains with only a few liters of water in my pack, was that ... it rained.

The account below is the one I wrote after completing the walk. The pictures are from the recent trip.

The weather isn't much discussed in Oman, not because it's any great secret, but because the weather in Oman is usually sunny from day to day. However, this is not always the case. The following appeared on the front page of the Oman Observer on Sunday, April 5th, 1992, under the heading "Showers Continue":

"MUSCAT - More rain fell over the Capital and most other parts of the Sultanate yesterday. The showers followed Friday's intermittent rain and Thursday's heavy downpour. The Seeb weather office last night forecast cloudy skies and scattered rain and thundershower to continue today in Northern Oman. Some areas might receive heavy falls, it added. The Southern Region would also experience overcast skies and heavy rain. Thursday's downpour, one of the heaviest in recent years, saw several areas and roads in Muscat totally inundated. Wadis virtually turned into rivers and traffic came to a standstill at many points. Cars being swept away by the gushing waters was a common sight."

And this was on the front page of the Oman Observer on Monday, April 6th: "Meanwhile, three days of incessant rain in Nizwa, the heaviest in 12 years, resulted in the drowning of two people, an Omani and an expatriate. Several people stranded by the floods were rescued by police."

Chris's daughter, who stayed at the house of an expat involved in helicopter operations while Chris was in Wadi Bani Auf after taking me to Hat, says that her host told her that the number of drownings was closer to nine. An Arab whom I picked up hitchhiking told me that he had read in the Arabic papers that 10 people from one family were killed in a single washout.

****

|

|

We met these two gentlemen not far above Hat, on their way down from the mountains we were entering. Note the footwear.

When the unusually heavy rains hit on Thursday, I was following an illiterate shepherd boy up a mountainside to his village of Kawar Zamm. It had been an alien encounter - simple peasant boy with ingenious manner meets ungainly city boy in surroundings familiar to the one, hostile to the other. |

I first saw Ali as he drove his laden donkeys past the pair of cars that had brought me to Hat, a typically Omani off-road village of perhaps two dozen houses. My friends had let me ride along on their outing up Wadi Bani Auf, though I had directed the last bit, referring to my maps to make the expedition take the low road of the two gashed out of the moonscape mountains. At 1100 meters, Hat was as far into the jebel as you could drive from that direction up Wadi Bani Auf. From there I intended to walk east over the mountain to Qayut, whose approach from the south I already knew - or if things were going well, to continue east over unfamiliar terrain and try to get myself out Wadi Bani Khurus via the landmark pass at Aqaba Talhat, whose approach from the north via one of the most impressively engineered sets of stone steps set in any mountainside in Oman I also knew. Having some familiarity with the terrain, and equipped with an altimeter on my watch and compass as well as a set of maps obtained for me some years ago by a running buddy in the military, I had no qualms about setting off alone into the wilderness for what I expected would be either a one or two night trek, depending on how I felt as things developed. No qualms that I let on, at any rate, as I bid my friends farewell and watched them grow gradually smaller as they drifted further below my mountain walk. But in fact, I was concerned about the skies, which were a little gray for walking in Oman. The mountains had been cloaked in cloud as we drove that morning from the capital to Rustaq, where we met the second car which had driven down from the Emirates, and whose occupants reported having driven through heavy rain the whole way. Driving into Hat at 2:00 that afternoon, rain drops had been sprinkling the windscreens of the cars.

I was grateful to have caught up with Ali and his two donkeys within half an hour of starting out. From the outset, I had had no clear idea of where to go. I had accosted a silver-bearded old man in Hat who had told me the way to Qayut was straight and up. When asked the way in the mountains, Omanis will typically point into the tortuous wilderness and say "saieeda, saieeda," meaning straight, straight that direction. Thinking it more logical, I decided to walk around the first low hill, but the old man intercepted me and more emphatically told me to head up it. I did, and I soon saw that the way I had started out plunged behind the mountain to depths best not contemplated. It was also typical of the wildly dramatic Omani countryside to upfold and plunge in ways requiring hours for the unwary to extract themselves.

At the top of the hill, I found the trail, and I caught Ali and his donkeys ten minutes further on. During a short chat, in which Ali seemed relieved that I could speak some Arabic, we ascertained that Ali's village, Kawar Zamm, was on the way to where I was going. We didn't exactly agree to stay together on the trail, but Ali kept glancing back over his shoulder as if to check on me when he would pause from marching nimbly in his rubber flip flops to adjust the halters on his donkeys. The harnesses were fashioned from goat's wool and adjusted with goat-hair rope, and they passed just beneath the donkey's tail so that the constant stream of droppings fell into the harness before working its way to the stones. I struggled to keep pace with Ali's pack train, stopping only to get out my reliable old army surplus poncho when the rain stopped evaporating off my t-shirt right away. I've had my poncho for 20 years - it has holes in it where ants ate through it in Africa. Unfortunately, it's seen a little too much wilderness, and has torn and taken on a disturbingly sieve-like character of late.

Ali's trail provided great views both behind and all around as we ascended. It was well worn and easily followed - Ali later told me he made the trip into Hat every two days for "ration", one of the several words, like "sleeping bag", or "light" for flashlight, that the people of Kawar Zamm had imported into their Arabic, probably because the villagers worked occasionally in the "jaish", or military, practically the only source of cash for "ration" in the impoverished villages in the Jebel Akhdar.

Ali's village was perched atop a tongue of granite at 1500 meters, and its half-dozen stone houses practically blended into the mountainside. I was hoping to be asked to stay a while, because the rain had begun to fall in earnest, but the few villagers about, ramrod thin men and hardy women dressed haphazardly in colorful village dress, obviously had little to offer - and because it was Ramadhan, there was no invitation to dates and coffee, just Ali asking me what I was going to do. With the burden on me, I didn't wish to impose, and so I asked the way to Qayut from there. Ali pointed up the mountain, but by then a huge cloud had obscured all but the base. Still he led the way as if to show me the trailhead. With the rain quickening, I was going through the motions of polite departure when another villager intercepted us and asked what the hell I was doing starting out into what was quickly becoming a rainstorm. He urged me to stay, and I allowed myself to be persuaded.

As the rain started down in sheets, we retreated to a shelter comprising two straight stone walls and an earthen roof supported by milled wooden beams brought up from Hat on Ali's donkeys. As lightening flashed and thunder rolled across the land, we were joined by a quick-looking Arab, Khalfan Said bin Mubarak, wearing his khaki army sweater over his rough dishdasha. During the time I was trapped by rain in that shelter, I had ample opportunity to admire the way the stones had been laid so carefully that the cleaved edges formed an interior wall remarkably flush considering the materials to hand, and Khalfan was the builder. He apologized however that he had not had time to sufficiently reinforce the roof which he accurately predicted would soon start leaking. This proved to be a minor inconvenience compared to what happened after another hour of even more intensive rain, when water started running in off the land and coursed through the open-ended shelter. At this point, Ali suggested a move to a more secure location.

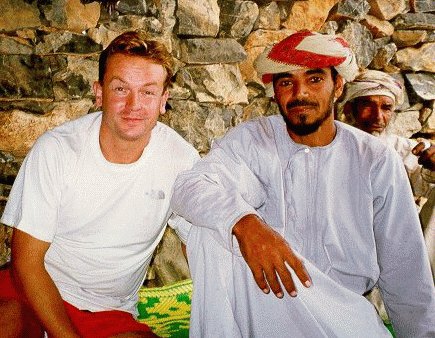

Paul enjoys the shade of Khalfan's shelter on our later trip. The shelter has had a rear wall added and is now the subleh, or place to receive guests. That's Ali's father on the right, in the background.

We rushed through the rain to another of Khalfan's creations, a stone "subleh" or guest house, which was protected from flooding by a dike of stones, and comfortably furnished with a mat on the floor which kept occupants off the water let in through the small window at one end and the single leak in the roof. The window and cramped doorway, with a gate of parallel upright sticks supported by rag hinges to keep animals out, let in just enough light for me to make out that the subleh was appointed with well-used blankets and woolen donkey harnesses - the kind that pass redolently behind the donkey. The subleh had tree-branch pegs set into the stone walls on which I could hang out my poncho, and it kept me warm and dry for the next half-day in a world that had unexpectedly turned to water.

Ali lingered on in the subleh a while. His face was a fine-featured study in ingenuity, making him impossible to dislike. In the silence between conversation I would find him staring intently at me, bemused at his discovery. Wondering how unusual it was for a westerner to be there, I asked him how often people like me happened by. He said that no westerners ever came to his village.

After a while, the rain began to let up, and I glanced out the door and realized that the loud rushing of water I had been hearing was not the sound of rain, but the sound of half a dozen waterfalls rushing off the face of the gorge opposite the subleh. Ali came to the same realization and let his face betray concern for his goats whose ubiquitous bleating had taken for him the same frantic tenor a mother might detect in a newborn, and he excused himself, telling me "istariyeh" which means sit, and for a visitor to an Omani village, it means stay where you are until we return for you.

But I wanted to see the waterfalls, so I put on my poncho and went out onto the granite balcony over the gorge to watch my first flash flood. Perhaps a hundred meters below me, the gorge remained dry at its lower end while water rushed down from the top. The water came in falls, building momentarily at each ledge to spill noisily into the next. Eventually it reached a level of porous gravel which delayed the flood until the water table became saturated, at which point the oncoming rush started to stir the earth into an ever-widening whirling caldron. A pool quickly formed and then spilled over the top. Roaring like a train, the bottom of the gorge soon became a river, stranding the goats crying from the other side.

I watched this until the rain and chill drove me back to the warmth of my subleh, where I read in the doorway until sunset. By then the rain had stopped completely, so I climbed above the village to get a better view of the clouds dancing dervishly up from valleys obscured below. Overhead, the air was crisp and clear, but the clouds puffed like thick cotton from the lower altitudes and made valiant attempts to swirl into ours, without success. I had hopes the rain was ending; the earth was no longer awash with water flowing everywhere underfoot as it had been on my earlier walkabout.

The village dog, which had long ago singled me out as a foreign presence there, pursued me barking at a distance, so that the village men praying outdoors in white dishdashas donned for the occasion would be always aware of my movements, and so I returned to the subleh to await the pleasure of my hosts. With the onset of darkness, I expected an invitation to join the villagers, but it never came. Instead, the men and boys, their work delayed that day by the deluge, sortied with flashlights to round up their goats, their beams punctuating the darkened hillside opposite the gorge. Another man descended a path to a cave below the village, and I saw from his flashlight beam where the cow was kept. In due time, I ate from my pack: salami jerky, an apple, a carrot, bread, dates, and nut and caramel snacks. And during that day and night I consumed only the half-liter bottle of water I had picked up as an afterthought from Chris's car. Because of the rain and cool weather my need for water so far was minimal - out of respect for local custom, I had without difficulty abstained from drinking on the trail and on arrival in the village until the time when drinking was permitted. I had four liters left for whatever trekking I would do from then on.

Ali wasn't there on my second visit, but I met his father

With nothing to do in the dark, I had already gone to bed in my sleeping bag when Ali appeared with two of his brothers. I invited them in and, hoping to be invited out, offered to help them with their roundup, but they had finished their work. I tried another approach to being invited outside the subleh: I asked if they did anything special during evenings at Ramadhan, but it was not the sort of village that had resources for special events, and the purpose of my question was not understood.

It was approximately the last day of Ramadhan, but the trick about Ramadhan is that nobody knows in advance when the last day is. Nobody knows that until the new moon marking the onset of the next Muslim month, Muharram, is either sighted or not. And that doesn't happen until evening on the last day of Ramadhan. If the new moon is sighted, then it's Eid, and everyone can rejoice and begin to feast and eat whenever they like again. And if the new moon is not sighted, then the next day is still Ramadhan, and fasting continues for another day. And because of the threat of having to do compensatory fasting if the Ramadhan fast is broken, the question of whether the new moon has been officially sighted is of vital importance to every faithful Muslim. So Ali asked me if it was Eid yet. I told him I couldn't possibly know. He thought I might know because I had come from the capital, and I was therefore a link with the outside world. Ah, I replied, but how could I know since I was at that moment in his small village, sitting in one of the stone houses fashioned by Khalfan Said bin Mubarak? Don't you have a religious person here in the village with authority to declare these things? No, he replied, the Eid was set by the authorities in the capital, and this applied to all of Oman. So I told him I was aware that there was a committee meeting that very night in the capital to attempt to sight the new moon. Didn't they have a radio they could use to hear the decision? They did, he said, but it was broken. And then it hit me how remote they were - they had no way of finding out whether they should all get up to eat before dawn or not, and whether or not to fast another day.

Knowing that other villages in Jebel Akhdar were supplied regularly by helicopters that called twice a week, I asked if doctors didn't call occasionally. Ali said that helicopters called only in case of emergency, I suppose because Kawar Zamm was accessible in only an hour and a half from Hat. Then he asked me if I had any eye medicine. I didn't, but I asked who needed it. Ali said he did; since he was a child he had only been able to see out of one eye. I asked Ali if he had ever been to a doctor about it, and he said he hadn't. I asked him where the nearest eye doctor was, and he said Awabi, the big village at the mouth of the next wadi over. Since he went regularly to Hat, where there was a road and transport, I asked him why he didn't go to Awabi. It would cost a rial, he said. I told him I would give him a rial tomorrow - I didn't want to get my money out in front of him and his brothers.

This was when I found out that Ali and his four brothers were illiterate. Whenever I had asked any of them about school that day, he would answer simply that he herded goats. Now I asked them if they could read, and they replied no, they just herded goats. None of them had never been to school. But there were kids in the village who went to school in Bilad Sait. In that case, they lived in Hat all week and couldn't herd.

Although they never said so, I gradually became aware that I had their bedroom. They couched their questions in the politest terms: was I warm in my sleeping bag? Did I need any more blankets? Did I need this one here? Not sure of the drift, I said no, I was fine, I didn't need anything, I carried everything I needed with me. So they took all their blankets to the next building over where they put themselves up for the night.

I slept well in the subleh despite the continued attentions of the dog, who kept coming to the door and barking until he would forget what he was barking at and wander off. After a while he would wander back by, pick up the scent again, and launch into another round of barking. Sometimes when he woke me up, it would be raining out, and then I would appreciate how lucky I was to be spending the night there and not out of doors somewhere. I wondered what I would have done had I actually been put on the trail to Qayut that afternoon, how I would have weathered an intense three-hour thunderstorm. I was safe and dry, but I worried about my friends in the two cars, and if they had been caught by flash floods on roads that were prone to being washed out, and I imagined that wherever they were, my friends must be worried about me. And I wondered what I would do in the morning if it was still raining.

|

|

Before six the next morning a goat bleated close by, and this woke up the dog who had been sleeping for the past couple of hours but who suddenly remembered me and came around to give me a wakeup call. I quickly packed, snacked, and wandered outside. I could see no one around the village anywhere. Even the kids had departed from the next room, possibly having arisen before dawn to take their last meal before their last day of fasting. I didn't feel the people there were inhospitable not asking me to join them - they had ascertained that I had my own "ration" and were obviously living off meager resources themselves. They had contributed to my survival and asked nothing in return, and I had taken nothing from them except a room for the night.

|

|

My latest leave taking from Kawar Zamm was better attended than the first |

I shouldered my pack and tucked a rial note in the doorway of the subleh, though I doubt that Ali would be able to use it to get himself to Awabi to see a doctor even if it were he who found it. As I left up the mountain the way that Ali had shown me the day before, I heard bleating coming from across the gorge. I turned, saw two figures there, and waved. I couldn't make out who they were, but they waved back. They were the last people I would see that day or the next.

It looked that morning as if the rain might hold off for a while, and I was able to follow a trail for perhaps half an hour up the mountain. But clouds soon formed over my journey, figuratively and literally. The literal clouds would come and go with little predictability and varying intensity throughout my trek, as would the figurative clouds - during the next couple of days, my elation at apparent success would be punctuated intermittently by the clouds of potential disaster.

Uncertainty came, as I marched out above Kawar Zamm, first in the form of blasts of rain which I warded off with my poncho, and second, over which way to go. The trail had tapered into a dry spillway strewn with boulders, at which point I lost it. Deciding which way it continued was important, as whichever way I chose would commit me to the mountain right or to the one left, and only one was the right way. Going on instinct and perhaps some faint indication that a person had once passed that way, I chose left though it meant crossing the spillway (why else would a trail lead into a spillway except to cross it?). Breathing hard against the strain of working my way uphill, I eventually saw that the mountain immediately to the right was standing by itself - to have come this far that way would have meant I would have had to then drop down before going up again, either that or backtrack. The way I had taken on the other hand headed smoothly upwards toward what developed to be a gap in the mountain range that rose to 2200 meters further to the right, behind which, according to my map, lay Qayut.

In my conversations with Ali the day before, when I had asked him the way to Qayut, he had said to go straight, straight until arriving at a "rabtah", at which point I should veer right. I hadn't understood the word "rabtah" and had asked him to explain it to me. It was fortunate that I had taken the trouble, because I was now clearly at the rabtah, a level plain at the top of the gap, sparsely green with grasses spawned by the recent rains.

Both figuratively and literally, the skies were again clearing on my trip. The intermittent rain hadn't seriously threatened and showed some sign of dissipating. My location was clear to me and I was again following a trail.

Walking with this on the right, it's clear that the trick is to get up it

As I reached the high point in the rabtah, I climbed a knoll and sighted what I assumed must the familiar gorge of Wadi Haslah, which I had seen on two previous trips from Qayut. But as I hiked nearer the gorge itself, the trail disappeared, leaving me to make my own way over the rocks toward the edge. As I walked, I recalled what I already knew about the gorge. I had been there twice before, once to Aqabat Zufur on an overnight hike with Mike Douglas, which I could even then see as a sagging depression in the wall of rock across the gaping crevice, and once atop the cliff face itself on a walk with Maryse, a friend I'd taken on a day's outing just beyond Qayut. Maryse had twisted her ankle on the mountain above the cliff and for her pains had been given a fine walking stick by the concerned people in Qayut to aid her down the mountain. I was using the stick at that very moment. Incalculably useful in keeping balance and preventing injury, it had a rounded natural wood knob worn smooth by countless palms. To return it, and to deliver a copy of a photograph that Maryse had taken in Qayut, were two reasons I felt I would be welcome on my return there.

The gorge of Wadi Haslah ends in a semi-circular sheer wall of rock cliff face towering over the village of Halhal tucked away in its base at the end the wadi. Just to the east of Halhal are some houses placed on terraces slightly up the cliff face, and it is from there that the only possible trail climbs to Aqabat Zufur itself. Standing at that spot, Mike Douglas and I had tried to discern a way up the walls on the west side, which Mike had already attempted without success with another friend, Rob McKinney. I had also been to the lip at the back with Maryse and had seen no way down the vertical drops.

Remembering my previous reconnaissances of the wall of mountain to the right of where I was walking, and which I was soon going to have to climb, I started considering the cliffs further back from the rim. With prospects of finding a way up once I had walked to the rim being not all that good, I began to see little point in going there at all. I was thinking that perhaps I should instead go back from the rim and try to find a way up in more gentle country to the west, the way I had come. So I abruptly turned and headed up the mountain in the opposite direction.

Characteristic of the Jebel Akhdar, there was increasing slope up that mountain to about 1900 meters, at which point palisades rose the rest of the way. My experience suggested it would be a mistake to climb up to the palisades at some randomly selected spot because once there, I would likely find no feasible way up and not much freedom laterally, since each slope up tended to be like a giant's claw, and getting to the next one over required dangerous movement over huge boulders and loose rubble that tended to be worse higher up the steep interstices. Trying to climb the wrong claw only to be stopped at the palisades would probably mean a struggle up to 1900 meters and then a retreat back to 1700 before making another attempt up another claw, an exhausting scenario. So I was hoping to find a mountain slope back from the gorge which would lead above the palisades.

The steps are just to the left of the rectangular lump in the center. First time around, I started my probe to the right.

It was slow plodding for half an hour until I had gone above 1800 meters and could see that the mountainside I was heading up disappeared into space where I couldn't see it from below, but had assumed there was land leading to gentler terrain further west. Unless I wanted to descend to a place where I could remount that gentler terrain, I would have to probe the palisades from where I was, which was in effect some randomly chosen spot.

Now the weather and my mood began to grow threatening together. As I scouted the palisades above, looking for any possible way, I saw that what I had at first perceived as a single rock wall in the cliffs immediately above in fact disguised a towering sliver that had come away from main mountain, forming a space between them up which there was some rubble that I could climb. It was hard work scrambling up the rubble, and not entirely safe. I was breathing hard at close to 2000 meters when I reached as high as I could on any kind of footing. The rest of the way was sheer, solid cliff, impossible without a rope and crampons.

Rain clouds broiled overhead, compounding my disappointment. There was little to do now but go down. I descended 100 meters to where I could move over to the next claw. Probing the palisades on the other side to the giant sliver of rock which had fallen away from the mountain, I imagined there might be a way there. Or perhaps it was desperation deceiving me into perceiving ways to the top. There was no telling from below when a reach might be longer than a leg span, or where rocks made slippery from drizzle might provoke a disastrous fall. But I was compelled to follow through, so I ascended again to 1900 feet and, as often happens in Oman, and often when you least expect it, I found in that spot a set of steps - and not just a vaguely marked plank or two of slate embedded in what might be a considered a footpath, but a well defined set of steps bordered neatly with stacked rock banisters nestled into the space between the east side of the sliver and the mountain. Up the steps, I simply walked to the top with no further trouble.

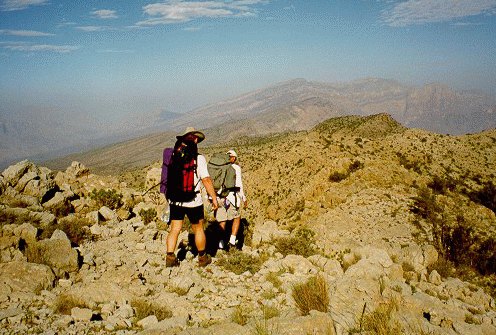

Second time around, we walked right to the steps. Here, Mike and I stroll up what I now dubbed "The Stairway to Heaven". Later we found that the British SAS had used this route as one of the assault paths on Saiq in 1957

It was raining by now and so I stopped to get out my poncho. Climbing up the nearest hill, I realized that I didn't have my canteen of water with me. I had left it where I had stopped just below. It wouldn't be the end of the world if I lost my canteen; I still had two liters of water tucked in my pack, and that was enough to get me to Qayut, where I could replenish supplies enough to get me down to Mahbit and the road gashed into the mountains above Tanoof. But I still had in mind maybe making the longer journey over to Wadi Bani Khurus, and loss of water would doom that plan. So I set my pack down on the hillside and went back for the canteen.

The episode illustrates how confounding it can be to walk in Oman, where rocks and mountains are homogeneous one to the next. I soon discovered I had no idea where I had stopped. All the rocks and acacia shrubs blended into uniformity with no salient features. Even the spot where I had left my pack was an indistinct blur, but the pack was luminescent green, and I kept my eye on it so as not to lose it too. When eventually I decided to retrace my steps, I even had difficulty locating the spot where the steps emerged over the palisades. Finally I found the sliver of mountain that had broken away and headed in the direction of my pack from there. I didn't succeed in finding my canteen until the second time I had done that, and then I only just managed to spot the strap. The canteen itself had fallen behind a rock, which was probably why I had left it behind in the first place.

This was only the first of several confusions to dog me over the next couple of hours. From the palisades, I decided to walk a little behind the gap where the mountains were lower than those ringing the gap itself, thinking to come out on a ridge overlooking Qayut while avoiding the highest climbs. So as I circled east and north, I kept to my left what I assumed must be the mountains ringing the gap while following those to my right which I assumed must lead to Qayut. But Qayut never materialized where I thought it should have. Instead, I wandered into terrain reminiscent of that over Mahbit, and from one point I could even see a road, which could have been the one to Mahbit or another one I had been told led to Al-Hamra, and which I had wondered about my last trip up that side of the jebel.

It was near mid-day and I was tired from my morning's exertions. The sun shown from clear skies, and despite the constant chill wind at that altitude, it was becoming hot walking. I was no longer sure of where I was or in which direction lay Qayut. The only sure option was to strike out for the road, which I could have reached in a couple of hours, and for a few minutes I seriously considered doing that. On the other hand, I could probably get a better idea of my location by climbing the mountain to my immediate north, though it towered a hundred meters overhead, and it might be wasted effort if beyond that was another even higher mountain, a common outcome in such circumstances.

Thinking I had nothing to lose but half an hour by climbing the mountain, I decided to do that, and at the crest I was treated to a familiar view straight down Wadi Haslah all the way to Wadi Bani Khurus at its mouth, and so I knew once again exactly where I was. I had been in approximately this spot on both hikes to the region before, and I knew now how to get back to Qayut and thence to Mahbit on the Tanoof road. Ahead of me, on the right rim of the gorge, I could clearly see Aqabat Zufur, which I had seen from the west rim earlier that morning, and from which I had walked a couple of hours with Mike. So I knew a little about the terrain in the direction of Wadi Bani Khurus. But beyond that couple of hours I wasn't sure, and there was nothing I could see from where I was that would point the way.

Mike and Mike negotiate the crest heading back toward Hat. Aqabat Dhufur is to their right.

And now it was time to make a decision, one that I was frequently unsure over the next day or two whether I regretted or not. To go to Qayut and down to Mahbit at that point would have been a sure way out. It had been a pleasant outing so far, and it would be some accomplishment to walk from Wadi Bani Auf over to Tanoof. But it was a way I had walked four times before. Plus, when I got to Mahbit, there was no guarantee there would be transport going down. There were only a few cars in Mahbit, and if their owners had other plans for the Eid, then I might be stuck with walking down to Tanoof, a substantial not to mention boring journey along a bulldozed scar in the land. To go that way would mean spinning my wheels in well worn tracks. In short, I wasn't interested.

But to go the other way was more than challenging; it was daunting. First, there was the freaky weather, but skies were clear at the moment, and there was nothing in the air to suggest that the rains hadn't exhausted themselves. Second, there was the question of water. There wasn't much left on the ground from the deluge of the day before, but I had used little of my four liters, and I figured I could stretch what was left to a two day supply, and I should be off the mountain by then. Although informants in villages frequently exaggerate, someone in Qayut had once told me that it should take eight hours to walk from there to Aqabat Talhat. I remembered his enumerating the passes en route: Aqabat Zufur, Aqabat Tanafudth, and Aqabat Talhat. Furthermore, friends Dave and Monica had made the walk, and their advice was only to stay as high up as possible. There didn't seem to be any reason short of becoming hopelessly lost or injured, both possibilities I downplayed in my assessment, that I shouldn't be off the jebel some time the next day. What the hell, I told myself, as I ate into my supply of snacks, go for it.

And so I did. At first, it went well. It was a longish walk downhill to Aqabat Zufur, where I stopped in the shade of a tree to take off my sweatshirt and walk in just my t-shirt, wet at the back from sweat. Near the top of the other side of the aqaba, there is a layer of mini-palisades. I had a little trouble there trying to go up at the wrong place, but I enjoyed the view and soon found the right way. From there I made my way up to the razor back at 2200 meters where there were astounding views down the gorge of Wadi Haslah to the left. It was then only a short walk along the crest to the gap where Mike and I had spent a brutally cold night our first walk into the region. I paused there to put my sweatshirt back on because it was getting cloudy again. I toggled my watch into time mode and saw that it was 2:30 in the afternoon. I was making decent time, so I paused for a snack.

On our previous walk, Mike and I had left our packs there and walked in about an hour to a spot where we could look down over the cliffs to a little town we thought was Masirat Shargiyin. Tucked a couple hundred meters down the cliffs at the base of a wadi, it must have been one of the remotest villages in the jebel. I remembered from that walk that just over the next rise from the gap, the land dropped into the wadi leading to the village off to the right. I wasn't sure what it did to the left, but I would soon find out. What I could see to the left was the line of mountains rising up to 2300 meters lining the gorge up to Halhal. I believed that if I followed the land inside those mountains, I would come to the village of Ru'us just to the west of Aqabat Talhat.

I continued into the depression beyond the gap where I had slept out with Mike and up the next rise to where I could look down on the deep wadi beyond. As I had expected, it appeared that I should traverse to the left and as I got stuck into that I saw trails going along both sides of the wadi below. That was encouraging and so I dropped the rest of the way down to follow them. The one on my side of the wadi, I expected, must lead into the village out of sight to the right, because there would be no way to go further east to anyone who had committed to that side of the wadi. The trail on the other side, I guessed, must lead to Ru'us.

To tentatively test my assumptions, rather than cross the wadi to the next trail over right away, I decided to follow the nearer path to the left away from the village. I expected to find some kind of crossroads where the two paths met, and I did. The crossroads was saliently marked with a cairn of rocks and a stick angling out the top. No one could have missed such a landmark.

But I wasn't going to the village, and as far as I could see, the trail I wanted went around the mountain when I thought I saw an alternate way up. Just ahead of me was a slope leading up to a spot a hundred meters lower than the crest which looked like it might take me to the other side while giving me the benefit of having a better idea of the lay of the land.

Walking in mountains gives insights into the universality of human nature. It interests me how I can look at terrain never having been there before and be in exactly the same position as the first person ever to go there who had to decide how to get from A to B. And the second person to arrive at that spot may have considered the situation and arrived at the same decision as the first, as did I, the nth. An excellent example of whatever forces of nature apply here would have been whatever logic that led me right onto the steps leading up the palisades. Going up this mountain slope, I thought I detected evidence of others having gone there: a footprint here, perhaps a pile of stones there. But it was hard to tell. Another universal of human nature is that people will try to believe whatever they want to.

Another trick of walking in mountains is the ability to read trails, and to distinguish human ones from animal ones. Goats roam everywhere in Oman, and their trails are thin and covered with their pellets, and I always think that anyone who follows one must have the mind of a goat, because they never go anywhere useful. Donkeys also roam wild in Oman, but their trails are thicker and again covered with their droppings. These trails may in fact be productive, because humans often drive pack animals. But pack trails will generally have a sandal print here and there, and the droppings might be mashed because of the way the harnesses fit across the rear of the animal.

My problem at this juncture was that I started thinking like a donkey. When I came over the crest I had mounted, well above 2000 meters, I saw below me a large boulder with a pool of water in front of it from the rains the day before and trails leading from there along the mountainside to the east. I assumed this to be a continuation of the trail I had marked from the landmark cairn, and I assumed it would take me to Ru'us, so it was in good spirits that I followed it for some distance until it started to get fainter and fainter as the slope of the mountain began to increase, and the land to unfold in an impressive panorama of deep wadis far below. Soon I had reached an area of boulders, and I had to drop down to some rubble below just to continue. The rubble was loose and difficult to walk in, and I had to drop lower to find footing. The further I went, the more I would have to drop, and the more I came around the mountain the steeper toward the vertical it became, and the less likely it seemed that this would get me anywhere but into the network of wadis hundreds of meters below, which is not where I wanted to be.

I sat down to have a think. It was by then 4:30 in the evening, and I was at a dead end. I studied the map but couldn't work out where I was - I have since realized that I was two kilometers farther west of Ru'us than I thought I was. Flustered and exhausted after ten hours of hiking, I had wandered out on a donkey trail. I found the culprits, four of them, and drove them before me as I retraced my steps. I had no idea about what to do next. It seemed I had already eaten dangerously into my margin for error on this tack, and I concluded that the best thing would be to abort my journey this way and get back to Qayut the next day, and then on to Mahbit and Tanoof as I could have done earlier that day. And what exactly had I accomplished? That was the pisser. It had taken me four hours to reach that point from where I had made my fateful decision earlier that day. I would be lucky to reach Qayut by noon the next. Essentially, the whole exercise was taking 24 hours out of my life for no reason other than to eliminate one means of achieving one of my goals: to transit Jebel Akhdar from Aqabat Zufur to Aqabat Talhat.

And once again, the vicissitudes of the weather corresponded with those of the trip. There was a cloud buildup to the west, and I was going to have to find shelter for the night. I must not have thought it threatening at first, because I passed a couple of likely rock monoliths on my way back to the rock with the rain pool before it that I had seen from the crest of the mountain I had come over. At that point, exhaustion suggested I stop.

I propped against the rock and relaxed for a moment. I had chosen my spot not badly. It had been used before: there was a pile of large chunks of wood left by someone, and plenty of little pieces about for getting a fire started and keeping it going. The rock itself had about a 70 degree slope to it, so I could tuck my rucksack out of any drizzle and hopefully keep dry myself. I had an hour of daylight left, and I used some of it to gather a little wood together, and the rest to get started on a meal.

I started to build the fire in front of my rock but then decided to move it under the overhang in case of rain. I wondered at the time if I would be bothered by smoke, but it turned out to be a wise decision. With wood dry from a day of sunshine, I had a nice blaze and a bed of coals before dark, and I put a couple of the big pieces of wood into the fire radiating outward so I could ease them in to provide fuel during the night. I opened a tin of steak bits and set this in the fire, and when it was heated I consumed it with bits of Arab bread. I ate a carrot and some cucumber and had some dates, and was thinking how nice a cup of tea would be and wondering if I could afford the water when I thought about the rain pool right outside my rock. Of course it was stagnant water and the donkeys must have been drinking out of it. Their crap lay all about. But if I boiled it AND chlorinated it ...

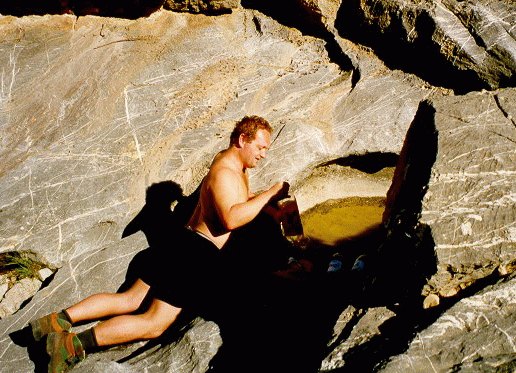

Mike fills up at the only waterhole we found on our walk in October. The rains were only just beginning then.

When I went over to the pool, I saw behind my rock that a storm was coming. There was lightning, and the first peals of thunder were about to reach me. So I worked quickly to rinse the tin that the meat had come in and fill it with slightly muddy water. I had it tucked in the fire when the rain hit. At first I sat comfortably under my rock and watched the drops hit the earth all around, but as darkness fell, the wind picked up and started to drive drops of rain into my face, and I put my poncho around me and my knapsack. As the rain gained intensity rivulets started streaming down the inside of the rock face and onto the ground, setting up an aggravating dripping on my things as well. The storm became spectacular. Sitting at 2000 meters, I was in the middle of the lightning, which crackled like artillery all around, bathing my world in flashes of blue strobe light. As the ground filled with water, it started streaming through my tiny domain. Fortunately there were rocks about. I set my rucksack on one and perched on my styrofoam roll with rocks for my feet and pants to keep them out of the water.

There was water and lightening everywhere. It was cold and I was forced to hunch up to stay dry. And through it all, my fire crackled merrily. The tin of water began to boil. I let it go for over ten minutes, till about a third of it had boiled away. Then, with the storm crashing all about, I nonplussedly had myself a nice cup of tea.

As the day before, the rain lasted for about three hours. Toward the end of that three hours, it was becoming tedious, to say the least. The wind was whipping about so that for a few minutes the rain would fall away from me, then the wind would shift and I would have to ward off the onslaught with my leaky poncho. The ground all around me was drenched. Water had even run through the bottom of my fire, soaking the coals at the base, but the big pieces of wood were of such quality that they stayed glowing and, with fanning and manipulation of fuel, flaming all night long. It was cold, and I got up when I could to warm my hands and dry clothes that got wet - steam would roil off them when I held them near the fire. But I didn't want to get my sleeping bag out in the rain - not only to keep it dry, but mainly to avoid having to carry it next day soaked with water.

While it was raining, I tried sleeping sitting up in my poncho, back against my knapsack to keep it dry, with my feet crossed on the rocks and my inflatable pillow wrapped around the hood of the poncho at my neck, but with little success. When the rain showed signs of letting up, I placed the rocks a little ways out so I could stretch my legs, and I'd stoke my fire for what little warmth it could emanate against the wind. I tried sleeping that way, but when the rain would suddenly come at me, I'd have to grab the rocks and pull my feet up under the poncho. But I was too cold to be able to really sleep that way, so when I finally saw stars overhead and lights from distant towns, probably Nizwa or Tanoof in the grand wadis far away, I spread the poncho out dry side up and laid the sleeping bag on that. The poncho wouldn't have had a dry side, except that the wind had evaporative effects on impermeable lining. Huddled inside my sleeping bag, I got warm, and I even slept for half an hour, but was awakened by rain lashing my face, so I scrambled up, stowed the sleeping bag in the pack, and resumed fetal position under the poncho until the rain let up once more. I played this game two or three times more that night, sleeping in the bag when I could, and sitting out squalls while coaxing my fire, until I figured the rain was not that great a threat anymore, and I took to sleeping with my back against my pack but feet stretched out in the bag and just throwing the poncho over the exposed parts to ward off raindrops. That was actually comfortable, and I slept soundly until dawn, by which time the cold wind had dried things off pretty well.

But when I crawled out of the sack at 5:30 and looked around my rock, I saw that my wakeup call was coming in the form of a raging thunderhead. Misty white-gray clouds were boiling up out of the valleys driven madly by a dark gray monster lashing them with lightning and shouting with thunder. In minutes it would be on me, so I went quickly into rain mode. I bundled my sleeping bag in my pack, placed my styrofoam roll beside it to sit on, arranged my rocks to keep my feet dry, draped my poncho over my knapsack so it would be protected while I could sit beside it with my head out the hood, blew my fire to life, and with lightning crashing left and right ran out to my rain pool, grown larger in the night, for a tin full of water which I placed in the coals and flame of my newly restored fire.

I sat back dry and battle tested to watch the water and fireworks and revel in the thunder even as it exploded like shellfire so close it made me wince and grit my teeth. Of the whole experience, electrocution was my only fear. That and the water streaming out of the mountains. Within minutes, water was forming pools around the rocks at my feet, soaking what little fuel I had left and discourteously threatening my fire and my cup of tea. I watched the water form falls off the nearby mountain. In no time it had formed a stream that headed naturally for the little pool outside my rock. I furiously fanned my fire as the rain raged around me. I hoped this wasn't another three-hour tempest. If it was, I wondered if I would be able to walk to Qayut in the rain.

But I was lucky. Within the hour, I was sipping tea and the rain was letting up. The little stream at my door carried a steady current of water but no more than that. The lightning was past and echoing about the mountain peaks to the east. The cold dry wind miraculously dried my poncho while I finished my breakfast of dates and granola bars.

Behind my rock, there were low clouds laden with moisture, but steel blue sky high above, so prospects were looking up for the walk back. One encouraging thing about a really thrashing rainstorm is that it reduces chances for another one in the next few hours, and though I had been delayed by the one just past, I hoped not to be thwarted reaching Qayut, where I could probably dry out even if I got wet along the way. And from there, I could be in Mahbit in two hours, with some possibility of starting home by car. I was still disappointed about having to abort my planned jebel crossing, but taking things a step at a time, I determined to get on with the task of getting back home.

The first act in retracing my steps was to climb the mountainside that would lead to the path down to the cairn with the stick out the top and then turn uphill to the crest beyond which was a fairly substantial hill leading to the gap where Mike and I had slept, then the walk along the razorback and then skirt down to the gap at Aqabat Zufur, followed by a slog to the high point at 2260, followed by a half hour across the hilltops to the mountain above Qayut, and a 45 minute walk down to the village itself, where I might see the smiling face of the buck-toothed man who had enumerated the gaps from Qayut: Aqabat Zufur, Aqabat Tanafudth, and Aqabat Talhat.

I was laboring up the hill, plotting my course to the trail back down to the west, and reciting the names Zufur, Tanafudth, Talhat in my mind, when it suddenly dawned on me. The gaps. I was meant to stick to the gaps. Not the inside of the mountains where I thought it ought to be, where I had got stuck the day before on some mythical donkey trail that would never reach Ru'us, but following the edge of the mountains where they plunged into the valleys on around to Talhat. And that was when I saw what my mind made me want to see, what might have been a trail going up the mountain to the east, to the crest at 2200 meters. Now it all came together: the cryptic message from the buck-toothed Arab repeating the names of the gaps because I had not caught the pronunciation the first or even second time; looking up the mountain from the landmark cairn with the stick pointing that way; up the mountain where the first man had looked long ago and said to himself in thoughts he had no language to articulate, it must be this way. The universality of human endeavor all pointed me in that easterly direction, and without much deliberation, for that had taken place already in so many minds over so many eons, I turned up the trail to see where it would go.

It led for perhaps an hour over some of the most spectacular scenery of my walk. To the north and to my left lay the incredible drop into Wadi Haslah. To my right were the drops into the network of wadis that had stymied my movement the day before. As the trail moved me inland, I saw that into these wadis poured countless, often spectacular, waterfalls, a rare scene for Oman. I was lucky to be seeing it. I felt like I was walking in Norway or Sweden.

My casual stroll soon ended on a landscape of massive valleys in all directions. To me who would have to find a way across, they appeared like potholes must look to an amoeba. I checked my compass and scanned the terrain for some hint of where to go and saw to the east discernible trails meandering up a wadi scattered with thorn trees. As I walked down, I heard the roar of water rushing off the mountaintops as it plunged off a precipice into the wadi hundreds of meters below. On the opposite wadi wall, another waterfall mirroring the action of the one before me plunged its torrent the full face of the towering cliffs, so I was treated to the spectacle of cascading water from two perspectives simultaneously.

I was concerned as I approached the wadi floor that the rushing water might prevent me from crossing to the other side, and I was relieved to find rocks that allowed me to hop over easily. On the opposite bank, I became momentarily confused. From below the trails, I couldn't see them, and I wasn't sure which wadi they were in. I went where I thought they should be without finding any obvious footpaths, until I found one leading to my right out of the wadi and onto the nearby ridge. Here the trail led along the rim of the gorge with its waterfalls. Though this was not the trail I had seen from above, I followed it because it was scenic, but when it began to peter out, I decided to climb the hill to my left and have a look from there.

What I saw was not particularly encouraging. Just below me, I could see the trails I had spotted from across the rushing water, but they led up to a donkey wallow and seemed to stop, or perhaps lead down into the valleys. The valleys themselves ran east, but headed down down down, not the direction I wanted to go. More north but running to the east and towering discouragingly overhead was a wall of mountain peaks I took to be those lining the abyss I was trying to follow. Clouds were swirling over the tops as I scanned them for potential routes. If I was going that way, I'd have to climb high, because each mountain had its complement of undulant folds of land rippling for rock-strewn kilometers in and out of granite crevices. I could easily become enmeshed in such terrain. On the other hand, following the trails to the wadis was risky; who knows where they might lead? Keeping to the gaps would be my only way of ensuring I had some idea of where I was.

Logic may be a factor in chance, as when you stumble on a set of steps leading up a palisade, or see a trail that you had crossed blindly the day before. But logic has no role in weather, and the weather now turned against me in a way I had not anticipated. I had accepted that I might get wet and cold, but figured I would keep my vision nonetheless. But now the clouds dropped down around me and robbed me of my view of even the next ridge over. For the next several hours, I would remain totally socked in. Looking back on it, I can see how lucky I was to have had that opportunity to have one last vital glimpse of the terrain and formulate a viable plan.

I now had a serious problem. It is essential when plotting a course to look at the lay of the land. Sometimes, you will study the terrain and decide to climb this hill to get over to that ridge connecting it with the next bit of high ground over because you want to make it up to that gap in the mountains yonder which will put you in the distant valley you think you ought to be in. Without distant vision, you risk going uphill only to be surrounded by valleys requiring hard work to get down and up to where you want to go which you can't see anyway. Do that more than once and you've spent a morning or afternoon going nowhere. Avoiding that fate by in fact going nowhere is not a reasonable option. On a walk a few years ago, my partners and I were socked in from the time we woke up until mid-afternoon, so to wait for clear skies could mean spending the night in that spot. My food was holding out well and there was water everywhere, but shelter was a problem, and I never really considered staying put.

Fortunately, I had the wherewithal to fly on instruments. I had my altimeter and I knew how high the mountains were. I had a compass and map, and I had glimpsed the lay of the land and taken bearings. I could essentially do three things: go north, go east, and go up.

This is what mountains are like in Oman: grasp a tablecloth between the fingers of your two hands and hold it before you. Notice how the folds are close together near your fingers but spread far apart the further downhill they are. My strategy lay in climbing the nearest fold of mountain until it came together with the next, at which point I could cross over and then climb around that fold in search of the next. If I went as high as I could and as far north as possible, I should reach the cliffs dropping down to Wadi Bani Khurus. By moving also in an easterly direction, I would be drifting towards Aqabat Talhat.

There were two dangers with this strategy. First, it was possible that the folds of tablecloth I had glimpsed were not the whole picture, that the trail I had followed had brought me further inland than I had calculated and that there were other hands holding other folds further to the north, so that by climbing blind I might be going to the tops of mountains I would otherwise go around if I could see the mountains further over. And secondly, even if I did reach the rim and follow it, it was always possible to reach peaks plunging straight down into gaps that make forward progress impossible, and I wouldn't be able to see back far enough to be able to efficiently negotiate them. Of these two dangers, the latter was the most likely.

For the next few hours, I doggedly followed my strategy. It wasn't particularly pleasant walking, as I was moving constantly uphill, and in contrast with earlier that morning, it wasn't at all scenic. At best, I was surrounded just by cloud, but at times the clouds moved over in sheets of rain, soaking my pants legs and leaking on my clothes through my poncho. Water streamed down the mountains between the folds of the tablecloth, and soon my shoes and socks were soaked. At least by keeping moving, I stayed warm against the sunless wind. At one point I found a trail with footprints. Someone with hiking boots had passed that way before, probably someone on a military exercise since the locals tended to wear sandals. A war had been fought here 30 years ago. The hills of Jebel Akhdar are littered with rusted cartridges, heavy jagged chips of shrapnel, finned mortar casings, and the rusted rims of ammo boxes, still with their leather handles.

I followed the trail only 20 minutes, until it reached a point at over 2000 meters where it led downhill while mountain shadows loomed still to the north, so I left it and moved north and east up the mountains. Eventually, I reached 2200 meters and a drop-off to the north. I couldn't see anything to the north but impenetrable gray, and to the east the ground sloped downward, hopefully not to plunge into a gap. I followed the slope steadily down a hundred meters before coming to the abrupt drop I had been hoping not to find. As I looked about for a way down, a cloud drifted past lifting its ragged skirt enough for me to see over the edge to the north. The bottom was hard to make out, but it didn't seem as far down as it should be. Then the mist thinned enough to reveal a shallow wadi bottom and further to the north another mountainside. I realized then that I was not at the cliff face, but cruising some nondescript inland mountain ridge, and I would have to backtrack far enough to cross to that next mountain over and pursue my strategy from there.

When I did reach the rim, it was obvious; the ground fell away in a vertical drop. By then it was raining hard, and I sought shelter in one of the caves in the cliff face. As I sat there snacking on vegetables, fruits and nuts, and easing the last four hours of walking out of my cold wet legs, the clouds parted to let me see into the wadi over a thousand meters straight down, and along the cliff face wrapping around to the north, with a salient pinnacle at the end. Even from that height, I could see that the wadi was full of water. So it probably didn't matter that I was wandering around in the mountains - once I got down, the wadis would be impassable anyway; no telling how long I would be stranded in this rugged water world.

With the panorama before me patchily exposed in the lifting weather, I got out my map and located my position. The only spot in my vicinity with a north south face like that was marked Hutmit Shiyah, and the place I was sitting was near Ras Alinah. The wadi would have been looking out toward the town of As Suwayib at the end of a road to Awabi at the mouth of Wadi Bani Khurus. If this were correct, then if I marched east only a kilometer and a half, I should come out on the cliff face looking down on Wadi Bani Khurus itself, and by following that cliff face further to the east find Aqabat Talhat.

There was only one way to test this theory. Holding my compass before me, I started walking. As I marched, the clouds began to part, revealing a cleft in the land with left and right ridges. I chose left because it led truest east, and within half an hour, I was standing in brilliant high noon sunshine looking down the cliffs on Wadi Bani Khurus. Even from 2200 meters, I easily recognized the town of Hijar. In the crisp air, I felt I could almost touch it, though it was a kilometer down and several away. The sight came to me as a gift. I don't think I really believed until that moment that I was going to make it across the Jebel Akhdar.

Well, I had almost made it. I still had to work my way along the cliff face to Aqabat Talhat. According to my map, there was a fairly straight contour at 2000 meters, though looking at the terrain itself, I thought I might be victim of sloppy map work. Between me and the far ridges lay a deep valley, with more mountains beyond. But after descending 100 meters from where I was I saw that there was indeed a connection of land right at the cliff edge. And a dramatic piece of land it was, plunging straight down into a gorge. Once I'd reached it, I was afraid to stand too near the edge in case the wind blowing off the mountains might take me with it. Far below, I could make out the distinct winding of a trail, and I followed it with my eyes. Suppose I took this trail, I wondered, I could save myself the walk to Aqabat Talhat. However, at about 1500 meters, the trail disappeared into a crevice with steep sides. Suppose it rained and I got caught in there, I thought to myself. I decided to take the way I knew from Aqabat Talhat to Hijar. It was probably the right decision.

Still, I walked the trail right along the precipitous cliff face to about where it would have dropped into the gorge, but when I lost it in the rough terrain, I didn't attempt to relocate it. Instead, I looked to the next gap over, a not too difficult traverse away across the wadi side of the mountain face. But I decided against striking out that way, and moved instead toward the back of the mountain where the trail was heading as it emerged from the gorge. The trail was a fine one, easy to follow. It passed behind the mountains in view of the half dozen stone houses a few jebels away that I took to be Ru'us. It came out at the next gap, which was not Aqabat Talhat, nor was the next one over, which is where the trail ended. I hoped Aqabat Talhat would be the next gap after that, but had my doubts as it seemed to be too narrow. I couldn't have passed it, could I have?

To reach the third gap, I had to work my way in a traverse up the wadi. It was reminiscent of a previous walk, when Mike and I had made the hike up from the bottom of the wadi. On the opposite side was a trail leading, I am sure, to Ru'us. Things were beginning to look familiar, but the crowning familiarity is the sight of the square stone mosque built at Aqabat Talhat that is hidden from view by the curvature of the wadi until it suddenly appears only a hundred meters away. When I saw that, I was jumping for joy inside.

I sat for a quarter hour on the stone wall in the shade of the rough-hewn mosque and ate a can of Italian bean salad with Arab bread. I gave myself till 2:30, then started down the steps. The walk from Aqabat Talhat to Hijar was one I had made many times before. It is an excellent trail, with thousands of slab steps well marked with stacked rocks. In my opinion it is one of the remaining wonders of the world, as it must have required incredible effort to engineer without machinery. Going down takes about three hours, though in descending, I mark not time but altitude. There are shady caves at around 1680 and 1480 meters, and these were my first landmarks and rest stops. Going down, in stark contrast with the difficult climb up, it is easy to tune out exertion and just place one step after another automatically. All the way, Hijar pulls closer into view, and isolated cars moving in the wadi suggest transport back to civilization.

The descent going smoothly, I was at peace with the world and looking forward to the imminent end of the journey, though at 1300 meters it started raining a little and I had to put on my poncho. At 1200 meters, I could hear drumming in the village in celebration of the eid. At 1100 meters there was thunder in the mountains, whose peaks were turning ominously gray. At 1000 meters there was lightning and at 900 it started raining hard. Unlike the misty drizzle I had been walking through for the past hour, this new rain was a sudden downpour. Immediately I started getting wet, but I spotted a low cave right next to the trail and ducked into it.

Thus far on my trek I had stayed reasonably clean, and the sun that afternoon had warmed and dried me and my things. I had been comfortably walking, with not so much as a cramp or blister, and now at 5:00 in the evening and just 15 minutes short of my destination, I found myself in a cramped cave with a gritty floor that the water dripping off my poncho was turning to mud. My first thought was, hell, I'm going to wander into Hijar now looking like a tramp. As the rain gathered in intensity, my second concern was that if I didn't get to Hijar right away, I'd miss any chance at transport out of Wadi Bani Khurus to Awabi and home that evening.

Meanwhile, my attention was distracted by the fascinating formation of the second flash flood I'd been privileged to witness during this single trek. My cave was at a crook in the trail, so I had a view back up the mountain as well as down on Hijar below, and I could see the water come tumbling down from Talhat, building up stepwise until it crossed the trail just in front of me and continued down the wadi to the edge of the hill I was on, disappearing over the drop off the Hijar side. While I contemplated the spectacle of nature working wonders so close at hand, a tributary branched off and ran parallel to the first, hitting the trail at such an angle that it washed over its stones before rejoining the first flow in the wadi and adding its waters to what was now a waterfall over the drop off. At that point, I was thinking that I would get my feet soaked if I tried to move on, and so maybe it would be best to wait in the cave until the rain let up and the waters subsided.

But a rumbling from a third direction signaled an ominous development. This latest flash flood had formed a cataract just to my right whose waters, when they'd joined the rest at their point of convergence on my trail, turned that and the wadi at my feet to a raging river which, I now realized, had cut me off from Hijar.

Despite the drizzle, I left my cave to assess my situation. I went over to have a look at the third torrent and was suitably impressed by its volume and velocity. There was no way I was going to step into that river, at least five meters across at its narrowest possible point, treacherous, and of unknown depth. My only hope was that it would subside, or that there was another way down. I walked to the drop-off to check out the latter possibility, but was quickly disappointed. From where I was the rocks tumbled vertically fifty meters to the level of Hijar, and there was precious little daylight left to squander in rooting about for a way down that might not exist, and might at worst result in a bad fall in waning light. The rain was picking up, thunder was rolling in, I was already wet and muddy - if I was going to be stranded there for any time at all, I had better use the available time to find a dry spot. The cave I had just left was too cramped and muddy, not suitable accommodation for the discriminating wayfarer. Fortunately, the area was riddled with rocky crevices; there was only to find, and choose. I scrambled over rocks looking into likely spots, finding this too small, this not deep enough. Finally just uphill, I spotted a substantial rock overhang and headed for it.

It wasn't the Hilton, but it was better than nothing, which was about its only consolation. The wide overhang kept me out of the direct rainfall, but the floor sloped radically with only a niche or two that I could even sit in, and with no way of lying down. I perched glumly, watching the rain fall in sheets in the waning light, reflecting openly to no one in particular that if the first sheltering cave hadn't been in that particular spot by the trail, if I had gone on just another minute rather than running to that particular cave, if I could have perceived what was happening and crossed the river while it was but a stream, if I had left Aqabat Talhat at 2:29 rather than at 2:30, if, if, if, then I would have been a minute further on in my hike and I would have been across the spot where the flash flood cut me off, and I would have been drying off in Hijar right then instead of sitting staring at my nearly missed and unattainable refuge from a cold wet fucking cave.

Adding to my frustration was the thought that maybe there was a phone in Hijar I could have used to call home and tell them that everything was alright. With all the rain and with me alone in the mountains, I was sure Bobbi would be frantic with worry if I didn't get in touch that night. When I eventually did get home, it was worse than I thought. My kids disclosed that Bobbi had said that night that she was going to murder me.

The view from my cave was actually spectacular, and in more pleasant circumstances I could have almost appreciated it - I could see clear down the wadi, where a dozen waterfalls plunged beautifully from the hills. I could also see that even if I could have got to Hijar I was unlikely to have gone further that night. The water from those falls was flooding Wadi Bani Khurus, starting with the road itself. What few cars there were still out in the approaching dusk were creeping slowly in the flood and searching for alternative ways around the road.

The rain that night was the heaviest, most prolonged downpour I had ever seen in my 7 years in Oman. It came in sheets where individual drops became indistinguishable. As night fell over the wadi, I heard the electric generators come on in Hijar, but as the waters increased from the mountains, the sound of generators was drowned out by the rushing of the rising torrents. Frequent bursts of lightning illuminated the flooded watercourses, bloated ribbons of silver ranging down the mountainsides, and revealed their increasing magnitude. Soon, the neon lamps powered by the now soundless generators in Hijar faded to fuzzy specks as the rain became so dense as to obscure even light, and the only sounds I could hear were the hissing of the rain, the roaring of the waterfalls, and the rapid tapping of water dripping inside my cave.

My cave was rapidly turning miserable. It was impossible to escape the water streaming in off the ceiling, leaking in steady drips that eventually soaked my back and sleeves, so that every stitch of clothing, all of which I was wearing, was damp. The water ran down the slope on which I was uncomfortably squatting, soaking my pants despite my efforts to insulate them with my styrofoam pad (the water just leaked on to the styrofoam and ran down that). My feet slipped off rocks I was using to keep myself in position and fell into puddles until my shoes and socks were drenched. At 900 meters, it was not as cold as at 2000, but it was not balmy warm either, and by 8:00 my teeth were chattering uncontrollably. My poncho, soaked both sides, offered little resistance to the incessant rain but at least gave some protection against the wind. I hardly felt like eating. Rather, I thought I might go mad in a world turned inexplicably to water.

In an effort to cope, I tried to think of worse things that could be happening to me, and the only thing I could think of was being subjected to torture. But as the hours went on and the discomfort increased, including the racking cold, I decided that this was a form of torture, not only physical but also psychological, being delayed another twelve hours from dusk to dawn because of a single minute lost on the trail; i.e. twelve hours to go the last fifteen minutes to Hijar. During the four hours the rain lasted, it seemed that it would rain forever and ever. And there was no guarantee at the time that my plight would end next morning; what if it rained again then and refilled the wadis? Was there any way of calling out to the people in Hijar to come up and bring a rope? (And what was the Arabic word for rope? I wondered). And once in Hijar, how could I travel by car if the wadis were full? When around ten at night the lights went off in Hijar, I couldn't even hear the generators go off, a bad sign since it meant the water was still raging.

When at long last the rain finally stopped, the stars came out, and I moved out on a ledge outside the cave and stretched out wet into my sleeping bag. I just needed to get warm, I didn't care now what got wet. During the night, it rained off and on, forcing me each time to return to sitting under the ledge. But the rain always came from wispy clouds that never entirely obscured the stars, and soon I quit worrying about it. I got cozy in my damp sleeping bag, and watched the shooting stars, as characteristic of Oman as rainbows are in Hawaii. Lulled to sleep by the sound of the flood waters, I hardly worried that these waters had caused me so much frustration and misery.

Some time before dawn, I awoke too cold to get back to sleep, so I was awake when the first generator came on in Hijar; and I could hear it clearly. At that welcome sound, I packed, ate an apple, and walked down from my cave to the trail. The water in the wadi was completely gone; there was nothing obvious, not even a stone out of place as far as I could tell, to indicate that there had been a rapids here just hours before. From there, it took me exactly fifteen minutes to reach Hijar, by which time the sun was making inroads on the cool morning air through flawless skies.

There were very few people about at that early hour in the town as I wandered through in muddy jeans. I found an open door and asked a young lady standing inside if there was a phone in any of the houses there. She didn't understand me, but a few children gathered, and one told me that the nearest phone was in Awabi, at the mouth of the wadi. I thanked them and moved on. Further into the village, some other children told me the same thing. So my assumption that I missed calling my wife by minutes the night before seemed to be ill founded too.

There were only a few houses in Al-Hijar, and outside the last one was a young man. I greeted him as I approached, as is the custom in Arab countries. He greeted me and asked me where I had come from. I explained in Arabic where I had spent the night and why, and he was much amused. As I was about to continue on, the man invited me in for chai. I told him I would love a cup of tea, as I hadn't been able to build a fire the night before, but that I would want to try and stop any car that came by. The man said that insha'allah we would stop any car that came by, and he welcomed me over his threshold and spread a mat out on the clean concrete slab of his courtyard.

The man's name was Saif Mubarak. He was in the navy at Wudum, a base that I knew because running weekends had been scheduled there. He normally stayed at Wudum all week and returned home on weekends, but as this was the Eid, he was enjoying the week's vacation with his three small children. His wife, hovering in the background, brought us tea which was a mostly milk concoction laced with nutmeg. This was accompanied by a huge platter of wafer thin sweet bread, and followed by a plate of curried goat which was quite tasty. During our amicable conversation, no cars appeared, and so after my third cup of coffee I wiggled my cup inverted to signal no more (to have had a fourth cup would have been rude), took my leave, and continued down the road.

The next person I met was an Egyptian teacher of English who spoke to me in my language while I responded in his. His name was Mohammed Muntazar, and like me, he desired transport, though his clean dishdasha and slippers suggested he wasn't going looking for it. I asked him if he expected any cars to come along. He said not really, as it was the Eid and as there was so much flooding, he doubted there would be any transport, but he would wait a while and if nothing came, he would make his journey the next day. I told him I would walk further to increase my own chances, and I plodded on through a muddy part of the roadway.

Wadi Bani Khurus is a beautiful meandering wadi lined by mountains both sides. Water is plentiful in the gardens, the villages are green and pleasant, and the people appear content. Most westerners drive quickly by in their 4-wheel drives, but I was glad to be strolling that cool morning the better to appreciate the place and savor its tranquil atmosphere. And a glance up the mountains revealed landmarks that were a part of my wider experience, for example the cliff face where it was probably a good thing I hadn't taken the unfamiliar trail through the gorge in the rain the day before.

The water had damaged the road and there was almost no traffic - at one point, I passed a car mired up to its windows on one side in mud. I paused at a village where the people asked me in, but said I had just eaten, and by the way, do you suppose there is anyone here who would drive me to Awabi if I paid for the trip? I was told no right away, that the road was too bad. So I moved on, but was picked up not long thereafter by a government truck grinding its way to the hospital at Sital.

I asked the driver if there was a phone at the hospital, but he said there was not even electricity there, and that the nearest phone was in Awabi. I consulted my map and determined that at worst I had fifteen kilometers to hike to reach that phone, and I started hoofing. I'd gone perhaps an hour when a youth happened along on his way to Awabi to pick up his brother who had driven down from the capital in a salon car. He complained continuously about the state of the road and the fact that he was going to have to come right back the same way. I suppose the road was an inconvenience, but on the other hand, I could see advantages to life among the gentle people of Wadi Bani Khurus.